The first time environmental educator and visual artist Trudy Barnes saw buckwheat blooms carpeting the hills near her new home in Glendale, she was thrilled, “The white and rust is really eye-catching for someone who’s not used to it.”

Last August, Barnes and her husband moved to Glendale after more than two decades in Northern California. Barnes’ husband, Chris, decided to switch gears and leave software engineering to pursue a career in audio engineering. Feeling overwhelmed and dislocated upon arriving in the new location, Barnes discovered that learning about local flora helped her develop a connection and appreciation for the rich biodiversity of Southern California. “I learned that [Southern California] is one of the most biodiverse areas in the world. It’s so exciting and beautiful.”

California Buckwheat (Eriogonum fasciculatum), Tujunga Hills

Barnes worked with glass and printmaking for a number of years before she discovered her passion for textile dyeing while hosting a tie-dye themed birthday party for her husband in 2016. Enamored by the process, yet not quite satisfied with the results, she became curious about other approaches that ranged from traditional methods such as shibori (an ancient Japanese method of shape-resistant dyeing) to playful experimentation with foraged and found materials.

California Love: Summer Sampler

Hand-dyed cotton, grass, embroidery hoop and thread, 2016

In 2018, Barnes’ curiosity and experimentation culminated in an artist residency at the Women’s Studio Workshop where she explored embossing and dyeing processes. “Having both projects going at the same time was interesting to me,” Barnes says, “because while the process is similar, the materials and environments are vastly different.” Barnes gathered objects, both natural and human-made, to intimately observe, reflect on, and produce physical memories of her surroundings. “To me,” Barnes says, “the two projects made a complete picture of my time at that residency,” she said, ticking off the contrasts: One was outside, one was inside. One was natural, one was industrial. One was spontaneous, one was structured.

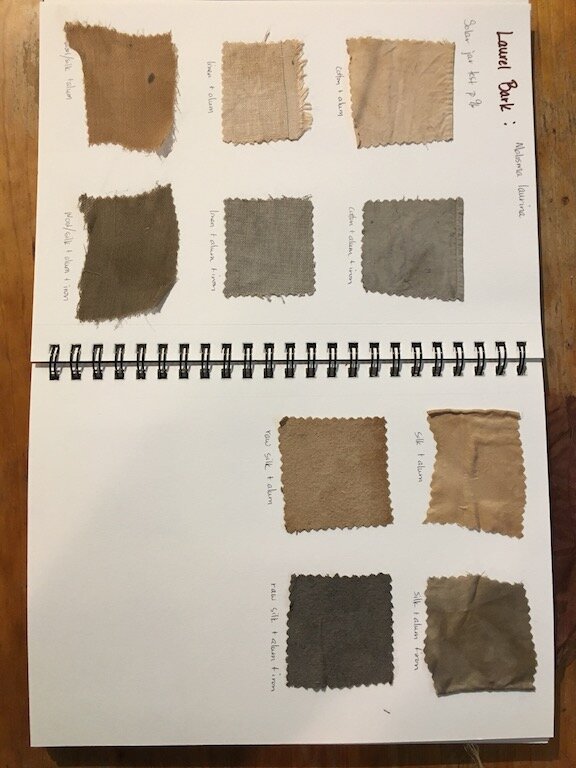

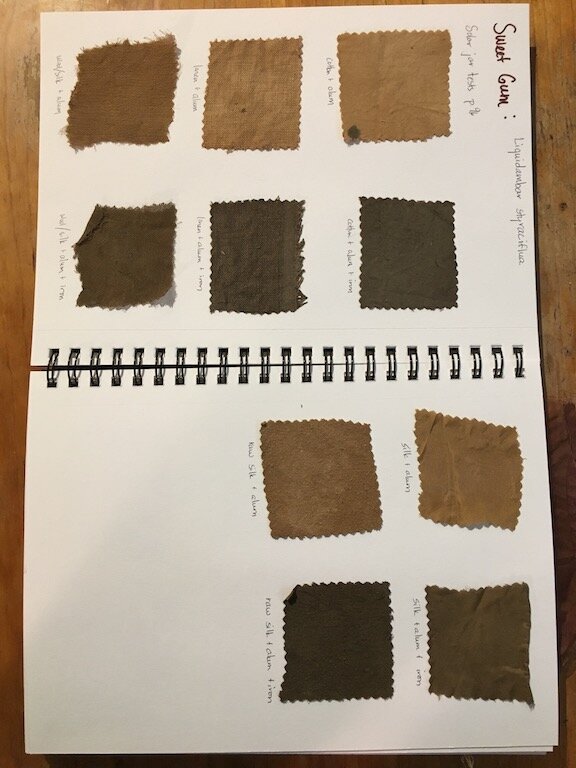

In Los Angeles, Barnes has taken her dying experiments even further. Connecting to the immediate environment remains a consistent theme in her body of work. “I’ve been trying to catalogue color,” Barnes says, “it’s a very exploratory process for me.” Barnes keeps a sample book in which she diligently documents her experiments: Opuntia fruit found on the ground during walks around her neighborhood yielded a burst of fugitive purples and greens before settling into subtle coffee browns, while invasive tree tobacco (Nicotiana glauca) from a park behind her house gave her a range of soft and rusty yellows to forest greens, depending on the color modifier used. Barnes raked up red leaves from her neighbor’s sweetgum tree (Liquidambar styraciflua) which produced bold shades of browns and grays while the highly invasive black mustard (Brassica nigra) taken from the same park produced pale yet satisfying shades of egg white and greygreen. “The color is pale but it feels good to use a plant that is so invasive” and that people want you to remove, Barnes says, “Who knew dyeing could be a tool for good neighbor relations?”

Mustard Dye Book - one of several process dialogues Barnes maintains.

Part of Barnes’ experience has been navigating the tension between using both native and invasive plants for her dye experiments, “When you’re working with invasives, people are happy for you to rip everything out,” Barnes says, “but there’s a lot of people that only want to dye with natives”. As gardeners are realizing the environmental and economic benefits of planting natives, they are also becoming more aware of the versatile beauty and traditional uses of native plants. As a result, they have become active participants in a rich and ancient story of textile making and dyeing.

Barnes’ recent class offerings at the Theodore Payne Foundation give all kinds of gardeners an opportunity to learn about native plant dyeing and responsible foraging. On the topic of foraging, Barnes tries to encourage gardeners to grow dye plants in their own gardens instead of taking from what’s left of our wild spaces, “I think it’s important to remind people of the extreme biodiversity we have here in SoCal and with that diversity comes a responsibility to try to protect it”. Barnes enjoys the process of designing natural dye classes for home gardeners, “It gets people to think about why they are choosing the plants they are using and that they serve multiple purposes” Barnes says, “I think it makes people think differently about their environment and what’s around them.”

Well aware of the environmental issues and the ever persistent Southern California drought conditions, Barnes does what she can to promote sustainability when experimenting at home, “To wash, mordant, rinse and dye,” Barnes says, “everything takes water”. Soon after she moved in, Barnes installed 10 feet of gutter on her roof which feeds into two 55-gallon rain barrels, “just a light drizzle sustained for an hour or two can fill the barrels…and almost all of it goes for dyeing.”

For Every End, A Beginning || Fennel and California Buckwheat dyed cotton, 2019

26” x 32” x 1.5”

Barnes’ most recent piece of work, ‘For Every End, A Beginning’ is a perfect example of the on-going, transitory nature of both artist and environment.

Here in her own words is the story of its creation:

“The panels on the left are all dyed with fennel, which was the last plant I collected while in Redwood City. As I packed to move, I took things to the local recycling center which was off the highway and surrounded by empty lots. The lots were filled with fennel and one of the strongest memories of moving are my memories of making that drive, the hot July sun baking the fennel so that the smell of anise was overpowering, the wall of green topped by the yellow blooms waving gently against a bright blue sky. I collected a box full of fennel tops and boxed them with the rest of my things for the movers to haul to LA. The smell of the fennel almost knocked me over when I opened that box.

“The panels on the right are dyed with California buckwheat, the first plant I collected when I got to Glendale. The hills surrounding my house were covered in a gradient from a creamy blush to deep rust. I had no idea what the plant was but fell in love with it when I got a closer look. The clusters of tiny blossoms were beautiful in their all their color variations and the bees loved them which made me happy. I had no idea what color to expect as I couldn’t find much information about dyeing with California buckwheat. Everything about dyeing with California buckwheat makes me smile, being in the hills to forage for it, the smell of the dye pot, which is so sweet my husband asked me that first time if I was making candy, and the rich colors it gives.

I brought the fabric with me to my residency at Vermont Studio Center and realized that fennel and buckwheat represented an end and a beginning for me. I made this piece to mark the transition I was going through.”